Design a hit counter

Today’s coding challenge is about designing a rate limiter in Java. We will go over 3 different implementations while discussing all the trade-offs for each solution, the time and space complexity and also a deep dive into the code.

Talk is cheap. Show me the code.

– Linus Torvalds

This an exercise I like both as an interviewer and as an interviewee due to the interesting discussions that might arise from each different implementation. There is no silver bullet, so regardless of which solution you choose to implement during an interview it’s important to know the shortcomings of it and how can it be improved.

You can find this problem named as hit counter in LeetCode. This code would be the basis for designing a rate limiting algorithm. Imagine that each hit received is a request coming to a server, and what we actually need to do is accounting on the amount of requests in different time windows and based on that we can determine if a request should be dropped or not.

Enough chatting, let’s jump into the code!

Using a Queue

Code

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

class HitCounter {

Queue<Integer> queue = new LinkedList<>();

public void hit(int timestamp) {

queue.add(timestamp);

}

public int getHits(int timestamp) {

while (!queue.isEmpty() && timestamp - queue.peek() + 1 > 300) {

queue.poll();

}

return queue.size();

}

}

Analysis

The simplest but also least efficient solution. Every add operation adds a new timestamp to the queue, so it’s constant time.

Heavy-lifting happens during get operations as there we need to remove from the queue the timestamps that are already expired (in the worst-case

scenario this means removing all the elements, so O(n) time complexity and also O(n) of space being held).

Another caveat of this approach is that timestamps are not compressed. We will have in the queue an entry per each timestamp even if they are repeated, this uses much more memory than just counting the amount of occurences.

Visualize the difference in memory consumption between a list like [1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1] to { 1 = 6 }. This idea takes us to our next approach!

Using a TreeMap

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

class HitCounter {

private TreeMap<Integer, Integer> tree = new TreeMap<>();

public void hit(int timestamp) {

tree.put(timestamp, tree.getOrDefault(timestamp, 0) + 1);

}

public int getHits(int timestamp) {

// Evict old entries

tree = new TreeMap<>(tree.subMap(timestamp - 300, false, timestamp, true));

return tree.values().stream().mapToInt(Integer::intValue).sum();

}

}

Analysis

This solution uses a balanced tree (TreeMap is implementated as a red-black tree) where the keys represent the timestamp in which a hit was detected, and the value

counts the amount of times a hit was received at that exact same timestamp. Because the tree is balanced, any hit operation

takes O(log(n)) time for updating the tree.

What about getting the hit count? Every time we want to get the amount of hits we first evict old entries that don’t fit in our 300 seconds window anymore by replacing the entire tree with just a portion of that only contains the entries that should still be counted.

For that sake we use subMap :

Returns a view of the portion of this map whose keys range from fromKey to toKey.

Note: While I was writing this post I got curious and digged a bit deeper into the API. Turns out that subMap is still backed by the original map,

so the entries are not being cleared from memory. But because we construct a new copy from that view, then the old map will be unused and then it can be garbage collected.

As an alternative, We can execute the following line:

tree.headMap(timestamp - 300, true).clear();This line gets the view of the tree that should be evicted (the opposite from the previous operation where we wanted to retain all the keys that should not be evicted)

and just call .clear() to empty that view of the map. By doing this we save the effort of creating unnecesary copies of the map.

Extra note

In the previous code we decided to execute our maintenace task (cleaning up the evicted entries from the map) just before retrieving the hits. We could have

also done it after the insertion of a new value. What changes? Well, it’s an expensive operation so here you need to discuss about which case should the

data structure be optimised for. Do we want fast reads and slow writes, or the other way around? In the ideal scenario we want everything to be fast, but in this solution

we need to make a compromise. Let’s check our third and final solution that solves this problem.

Using a circular array

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

public class HitCounter {

private int[] timestamps;

private int[] hits;

public HitCounter() {

timestamps = new int[300];

hits = new int[300];

}

public void hit(int timestamp) {

// Index in a circular array

int index = timestamp % 300;

// Overwrite evicted entry

if (timestamps[index] != timestamp) {

timestamps[index] = timestamp;

hits[index] = 1;

} else {

// Update existing entry

hits[index]++;

}

}

public int getHits(int timestamp) {

int total = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < 300; i++) {

// Count if inside the window

// Skip evicted entries

if (timestamp - timestamps[i] < 300) {

total += hits[i];

}

}

return total;

}

}

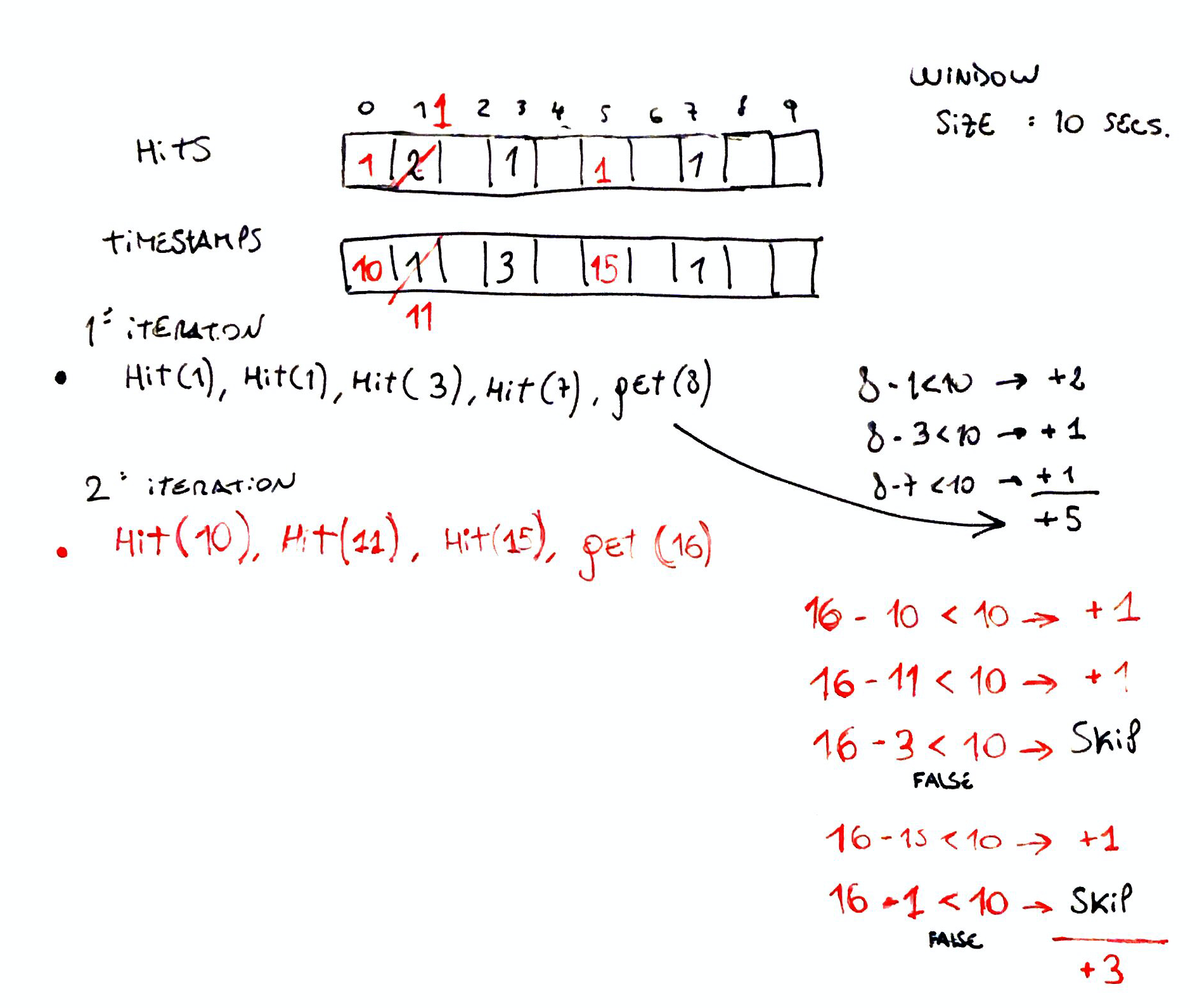

How does a circular array work?

A circular array is just an array, but the way we use it is what makes it circular.

Pay close attention to this line:

int index = timestamp % 300;Each timestamp will be mapped to a cell in our hits array. In order not to mix old and new entries, we will

keep another array timestamps where we store the timestamp associated to each index.

This extra array timestamps is necessary because without it, it would be impossible to tell if hits[5]

is refering to timestamp of 5, 305, 605, etc. The beauty of this, is that all each one of those timestamps

belong to a completely separate 300 seconds window, but they live inside the same array.

Still unclear? Let’s check a toy example with a 10 seconds window:

Analysis

The most complex (not really, just until you understand the secret behind it) and also the most performant solution. The amount

of space used is constant O(1). You might say, “Hey, that’s not constant, is an array of 300 positions!”. Well, that’s true,

but those 300 positions do not depend on the amount of hits we receive but only on the time window selected. Our algorithm

doesn’t care if we process 5 or 5 million hits, the amount of space used will remain constant.

Same applies for the time complexity of calculating the amount of hits. We aways iterate over the entire array to answer the query.

Conclusion

Are those the only solutions to this problem? Not at all, but those are the ones that highlight different trade-offs and strategies for solving this problem.

Comments